The Perennials Series

Crystal Mowry, Senior Curator at the Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery, invited me to create AR experiences that respond to the botanically-themed works selected from the permanent collection of the gallery. The four AR works in the series, Irises Listening, Eros Kissing, Mycelium, and Daes Eage, playfully draw upon recent studies of the communicative behaviours of plants and fungi through sound and enzymes. Spread throughout the gallery space, black and white symbols reminiscent of art nouveau design serve as fiducial markers, or targets, that allow visitors to experience the augmented reality content in specific locations using iPads provided by the gallery. The animated content reveals anthropomorphic botanical characters that are constructed from elements of existing plant life. Themes of animism and the flow of information via phenomena that operate outside of human perception are whimsically enacted within the interactions of the animated characters.

These works are preceded by a similarly motivated animation work, entitled Reception, which was created in 2015. Reception is an animated video projection created for an exhibition at the Gardiner Museum, featuring an evergreen tree comprised of arms and hands rather than branches and needles, glistening icily. Slowly oscillating between the gestures of offering and receiving, the hands are outstretched in a multi-tiered array, simulating the shape of the Grand Fir. The graceful patterns vary in their subtle movements, delineating the reciprocal nature of offering, inviting, and receiving. Reception also draws upon recent studies in forestry detailing the responsiveness of trees to stimuli in their environment, as well as the supportive and communicative relationship amongst tree communities. Imposing human anatomy upon an armature structure of a tree entails imagery that is contemplative of our human and non-human relationships, for example, the subtle repetitive movements of the branches alluding to the exchange of gases through respiration and photosynthesis.

The first of the AR animations the viewer encounters within the gallery space, Irises Listening, features the meeting of three anthropomorphic irises whispering to one another, shielding the message shared within their counsel from the viewer with their cupped leaf-hands. Framed within a leaf wreath, and standing before a black background, the figures are comprised of 3D scans of an iris flower, stem, and ovaries.

Irises Listening, Detail, Augmented Reality App, 2019

The communication of plants between one another and with fungal and animal species is another example of the transmission of information that fills the space about us, yet largely unseen and unheard by humans. In a field study, Dr Monica Gagliano has documented a crackling sound vibrating at 220 hertz emanating from the roots of trees, which in and of itself is perhaps unremarkable. However, the responsive nature of the surrounding plant life garnered the interest of Gagliano and her team. Nearby seedlings would angle the tips of their roots towards the sounds the larger root system produced.

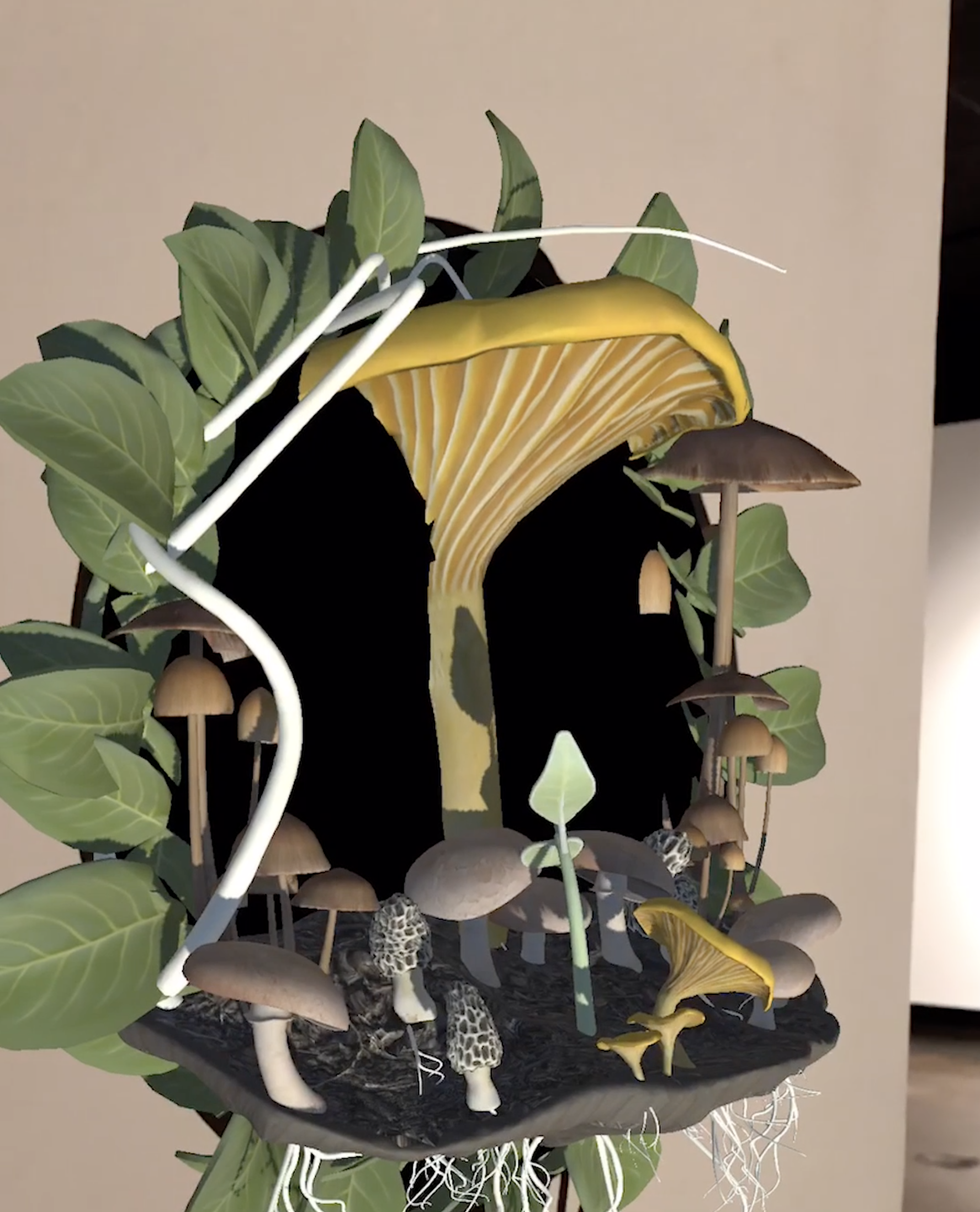

Mycelium, Augmented Reality, 2019

This physical response, as forester and author Peter Wohlleben writes, “means the grasses were registering this frequency, so it makes sense to say they “heard” it.” Upon experiments with roots of young corn and bioacoustics, Gagliano asserts that “plants detect and react to different sounds,” and furthermore, that the “emission and detection of sound may be adaptive.” (Gagliano, 2012) In these findings, Gagliano hypothesizes that sound transmitted and easily received in a given environment could potentially direct growth within the “swarm behaviour of growing roots” within short ranges, and can communicate with competing or symbiotic species to coordinate growth in a manner responsive to variable stimuli with immediacy in longer ranges. Gagliano lists numerous species with “listening” capabilities, including the tomato plant that releases pollen upon “hearing” the specific frequency produced by the buzzing of bees, and the chili plant that signals its seedlings to quickly increase their growth when in the proximity of their fierce competitor, fennel. (Oksin, 2013) Interestingly, only bumblebees and a few other select insects can release pollen in “buzz pollination.” Honeybees are unable to produce the vibration needed to unlock the pollen from the flower’s anthers, (Zimmer, 2013) yet one can recreate the bumblebee’s buzz, pitched at 400 Hz (or 24,000 vibrations per minute), with a tuning fork (Pearson, 2015).

Eros Kiss’ speaks again to interspecies communication, drawing upon the allure of the blossom as the reproductive structure of the plant to attract pollinators, as well as the use of humans to communicate using the rose, wherein the message is dependent upon colour. Yet, there is another facet of Eros’ Kiss. As roses encompass male and female organs in each flower, they are capable of self-pollinating, producing seeds that germinate into what many gardeners deem as underwhelming rose plants with smaller, less exuberant blossoms.

Gardeners will often remove the rose's anthers when the rose is a bud. Shielded under a covering, such as a paper bag, the developing stigma is allowed to mature slowly, whereupon the plant will be manually cross-pollinated with another rose plant to create a new rose hybrid. In Eros' Kiss, the rose is seen in an anthropomorphic embrace with its mirror self, kissing deeply to bask in the freedom of autonomy and unmediated self-pollination. The apps act as sculptural GIFs, cyclically engaging in simple interactions. In Eros Kiss, two identical anthropomorphic roses embrace, pressing their delicate petals into one another, as though kissing deeply. As they hold and tenderly caress one another, boughs of roses at their feet unfurl to stand erect, as though in a welcoming gesture and an expression of arousal. There is also a single-channel version.

The movement of plants and phototropism is also animated and personified in Daes Eage. This augmented reality animation is named after the old English term from which ‘daisy’ is believed to derive. Daes Eage, translates to Day’s Eye, possibly descriptive of the way the daisy opens at dawn. Daes Eage features several figures seemingly basking in an implied sun, some languidly, while others peer out of the augmented tableau, shielding their eyes from the glare, as though searching for the source of daylight.

Each app I created for The Perennials exhibition explores a different facet of communication or behaviour that points to plant consciousness. Mycelium offers an animated cross-section view of the symbiotic relationships operating above and below the earth’s surface, where the world’s largest living organisms, fungi, web their expansive roots called mycelium beneath the forest floor. Fungi and trees live with one another in partnership. The roots of trees produce soft hairs that the mycelium threads grow into, benefitting both parties as the trees that share their roots with fungi absorb twice as much nitrogen and phosphorus as those that don’t (Sigman, et al.). Fungi cannot produce their own food through photosynthesis as plants do, and so they rely on the long “underground cottony web” that grows beneath the stalk of the mushroom (mycelium) to absorb the sugars and carbohydrates that trees produce (Wohlleben, 2015). The fungi extend their reach throughout the forest, enveloping more tree roots, thereby gaining more access to food while filtering pollutants out from the tree roots, including heavy metals. Through chemical compounds and electrical impulses, trees communicate through the fungal roots, which serve incredibly as pathways of information between tree communities, and “operate like fiber-optic Internet cables.” This allows trees to send signals to one another, for instance allowing strong healthy trees to provide nutrients to saplings or starving trees, or to broadcast warnings of parasitic invasions. Mycelium plays an integral role in the health and nourishment of trees within an ecosystem. “Considering that entire forests are all interconnected by networks of fungi, maybe plants are using fungi the way we use the Internet and sending acoustic signals through this Web. From here, who knows.” (Wohlleben, 2015)

Cucoloris domestics is a video installation included as one of the works within the gallery’s permanent collection. In a darkened room, a potted philodendron sits upon the window sill. Beyond the plant, a bright, sky blue background appears to cast rays upon the floor of the gallery space, creating a shadow-silhouette of the philodendron. The shadow seems to be static at first, but as the viewer spends time in the space, they become aware of minute movements in the plant’s shadow. Tendrils curl, and uncurl, as though growing before our eyes. Like the minute hand of a clock, the movements are subtle. Viewers often look between the shadow and the plant upon the window sill, to catch the movement in both dimensions. The shadow eventually grows leaves and stems that briefly form an A-frame house, before furling up to a shadow that matches the physical plant.

[…] Cucoloris domesticus (2012) is another charming example of Norton's use of technology to conjure curious new worlds nested within the one we already know. I love the subtlety of this work and the way it prompts visitors who, like plants, stretch towards its light in an effort to feed their curiosity. (Mowry, 2019)

Several works from the Perennials were remounted at my solo exhibition, Not Present on the Year, at ELLEPHANT in Montreal, QC, in January, 2020, and at Hybrid Art Fair, in Madrid, Spain, presented by VTape in February-March, and was awarded ‘Best Exhibition’ of the fair.